Written by: Mickey Rogers PhD Student @ The Ohio State University

Every time I start writing about myself, I always bring up how much I love Lake Erie, as it is ultimately why I am here sharing with you today.

Growing up a “lake kid” meant campfires, golf carts, and catfish throwdowns. Every summer weekend was spent at our family “lake house,” which transitioned from grandma’s cottage, to a tiny nautical trailer, to an eventual house on the lake.

While the actual place we vacationed may have changed, my love for the lake never did. I remember collecting shiny sea glass and pearly white lucky stones. I remember when my dad and I would drive to the bait store for minnows, night crawlers, and waxworms.

But most vividly, I remember all the slimy green algae that would cover the lake, get caught on boat propellers, and pool up along East Harbor State Park.

I did not know much about algae at the time, but remember having a deep desire to know what it was and why some people liked it and others did not. I remember thinking, “algae is just fish food.” But as I got older, I learned some algae could actually be dangerous and that Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) were the source for many of my childhood memories.

As I did not have internet access at home growing up, I would go to the library after school and my googling would often lead to searches on “Lake Erie HABs.” I realized there were many strains of algae and depending on their environment, they could severely impact important resources like our water.

To understand these HABs more, I earned an undergraduate degree in chemistry and participated in environmental science and technology research. After graduating, I turned to graduate school in hopes of learning even more about algae.

I remember starting my graduate school application’s personal statement very similarly to this blog, discussing my passion for Lake Erie and algae, in hopes of finding a chemistry research lab that would give me the opportunity to learn more.

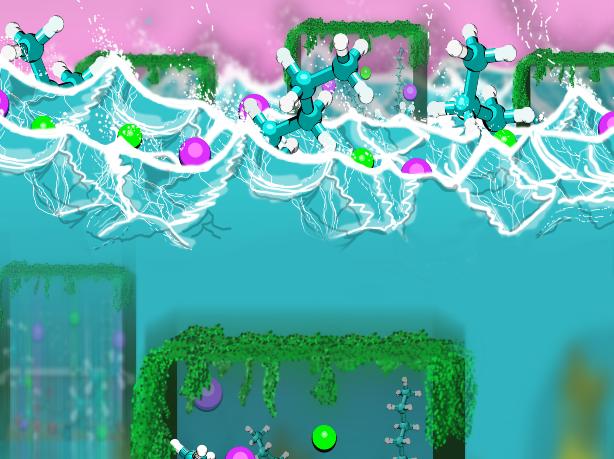

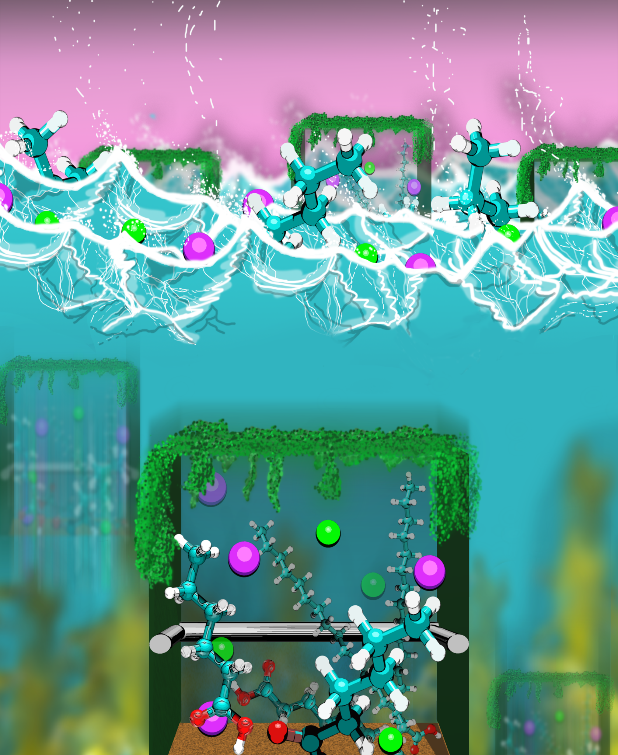

I was able to find that laboratory and I am currently a graduate student at The Ohio State University where I study how algae produce and release a range of different molecules that can alter the surface of the water overtime.

While I was introduced to algae by the lake, I have since learned that there is a lot of algae in our oceans and it plays a big role in important oceanic and atmospheric chemistry.

The ocean’s surface is really important to our climate as its composition dictates what molecules end up in our air. When the ocean surface is perturbed by wind or waves, the materials on the ocean’s surface get emitted into the air as sea spray aerosol. The tiny molecules inside these aerosols, including those released by algae, help to control important processes such as the warming and cooling of our planet.

To better understand how algae alter the composition of the ocean’s surface, I wanted to grow and literally see them for myself using a novel imaging technique in our laboratory.

And I did just this. In my recent publication “The Ocean’s Elevator: Evolution of the Air–Seawater Interface during a Small-Scale Algal Bloom,” I investigate how algae are responsible for the release of molecules that ascend to the ocean’s surface, our atmosphere, and beyond, ultimately earning algae the title of “the ocean’s elevator”.

Overall, the study uses powerful, surface-sensitive imaging and spectroscopy techniques to understand how algae change the water’s surface overtime. We found that algae release enough molecules over time to comprise a 5 nm depth of the water surface. This is 1/20,000 the width of a strand of hair. But compared to the ocean’s nanolayer surface, which we define to be roughly ~10 nm, this is half the width, alluding to a significant contribution to our ocean’s surface!

Additional studies in the publication show how proteins, released from algae, are observed at the water surface, meaning algal protein could end up in our air as aerosol particulates.

Knowing that so much of the ocean’s surface is composed of these specific algae molecules is extremely valuable in our understanding of algae’s contribution to our atmosphere and planet. If we do not take care of our planet, phenomena like pollution and ocean acidification will drastically impact algae, changing the composition of the ocean’s surface and sea spray aerosols. Sea spray aerosols are important to the regulation of earth’s climate.

So, by disrupting the role algae play in our oceans and atmosphere, we could induce long lasting impacts on the health of our planet. (https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00239)

The origin of this particular project is very important to my growth as a scientist. And although “The ocean’s elevator” has become an impactful study, it was born from a state of misdirection.

I was without a targeted research project nearly two years into my graduate program. I was preparing for my candidacy exam and was required to completely rewrite my proposal, throwing away months of work. I became very confused and highly uncertain about the trajectory of my graduate research.

I knew I wanted to work with algae and answer important questions relevant to our climate, but I was without direction. Luckily, Dr. Jennifer Neal, at the time a senior graduate student in our research group, saw my lack of confidence in myself and my science and stepped in to guide me.

She nudged me in the direction of using one of our novel imaging techniques to understand algae. In a matter of months, I learned so much from Jen.

I even learned the small things that no one mentions to you before you decide to embark on a doctorate adventure including:

- how to best organize your lab notebook

- which citation style to pick having first consulted the journal specs

- when to use a more complex software to organize and analyze technical data

- making an excel template for quick calculations to not waste time

- keeping track of the batch number of your chemicals in case something goes wrong

- why you should label your glassware because, despite what you tell yourself, you will not remember what solution you made later.

Graduate school can be REALLY HARD, especially when you are a rookie first or second year and have been tasked with developing a project completely on your own.

But what I learned is that it doesn’t have to be like this.

The real world is not going to ask you to cure cancer without giving you the medical resources and education to first tackle something like cellular biology. Why should graduate school be any different? As someone who is exceptionally interpersonal, feeling so lost and alone in my graduate program was debilitating.

But, as soon as I felt that support from Jen, as soon as I had someone to brainstorm ideas with and train me on the analytical techniques in our lab, I grew exponentially as a scientist capable of developing and pursuing my own independent projects.

In graduate school, there seems to be a stigma that asking for help makes you a lesser scientist. But through Jen’s mentorship, I became more of a scientist than I thought I ever could.

Now that I am preparing for the end of my graduate career, I am using my newfound confidence and independence to pursue other algal avenues. I am conducting experiments to expand my studies on algae and exploring careers in algae innovation, such as biofuels and permaculture. I am exploring science policy to understand the importance of lobbying for sustainable energy alternatives.

All these new directions were made possible by a girl with a love for a lake and its slimy green algae.