Written by: Audrey Carver, CAICE 2021 Summer Science Communication Fellow

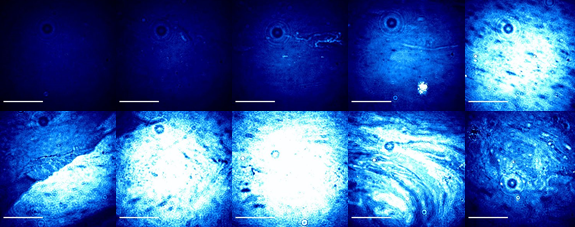

The Brewster Angle Microscopy (BAM) technique is easily Mickey Rogers’ favorite instrumentation and methodology at CAICE, so much so that her cat’s name is Bam.

Chris Jernigan, on the other hand, prefers the Mass Spectrometer, an instrument that serves as the basis for his research.

It seems as though most of the scientists working at CAICE have favorite instruments. This makes sense, as CAICE is well known for its innovative approach to instrumentation, often creating new tools or revamping existing ones to solve complex research problems and explore undiscovered topics.

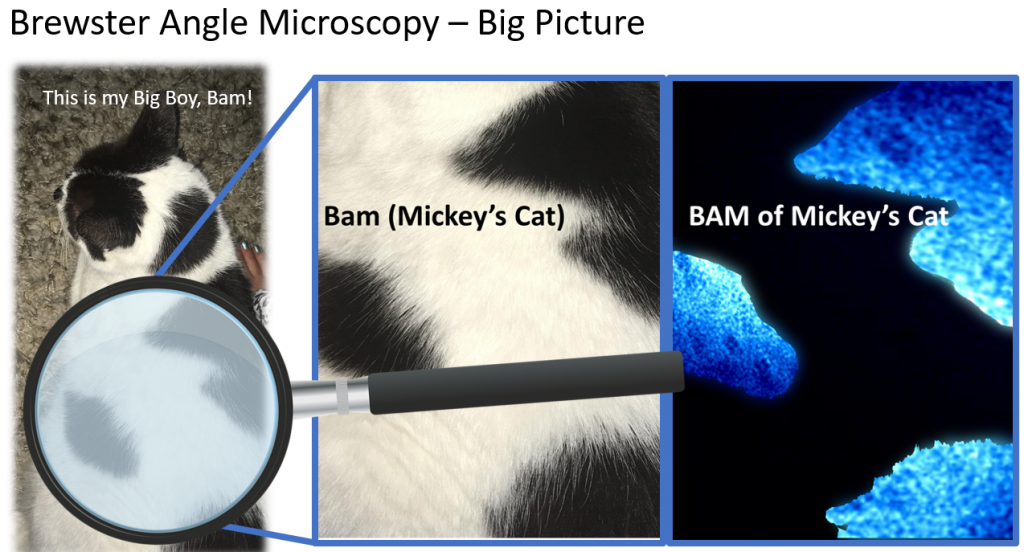

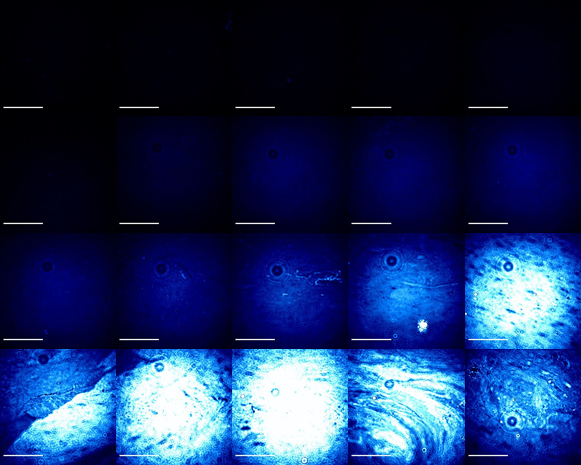

In Mickey’s research, for example, the Brewster Angle Microscope allows her to look at the surface composition of the ocean during algal blooms. It works by shining a polarized light onto the water’s surface at the Brewster Angle. When polarized light hits the surface and this specific Brewster angle, there is actually no reflectance observed from the surface.

However, when you measure a dynamic system such as algae, its exudates rise up and change the refractive index of the surface, allowing Mickey to capture actual images of the surfactants present at a nanometer interface between the ocean water and air.

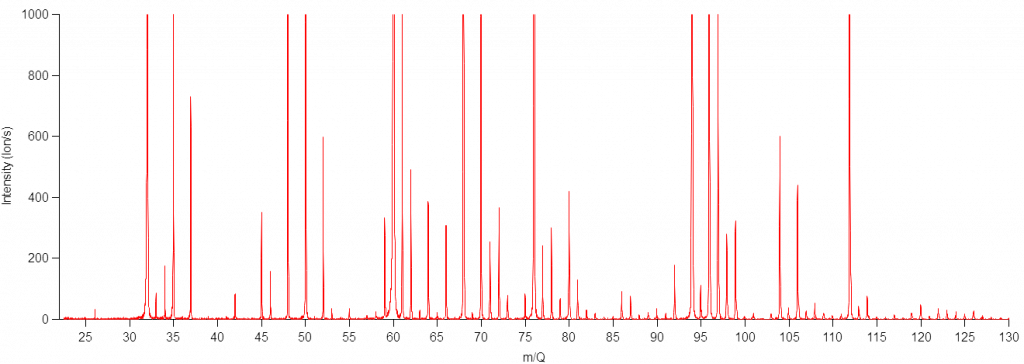

In Chris’ research, their custom built and highly specialized Mass Spectrometer allows him to investigate the aerosol particle makeup of the atmosphere by selectively isolating and detecting certain classes of molecules in the air. He focuses on the oxidation mechanisms of trace gasses called volatile organic compounds, and the pathways that these compounds take to change and react in the atmosphere.

Chris and his team use a process called chemical ionization to charge specific classes of molecules in the ambient air, place them in an electric field, and then measure the mass of these analytes by recording how fast they travel over a set distance.

Chris and his team then get to play a “fun guessing game” to determine which molecules are responsible for the unknown masses, allowing them to know exactly what is in the air. His team currently studies a newly discovered molecule, hydroperoxymethyl thioformate, only two years prior during an experiment like this one.

Beyond Chris and Mickey, CAICE is a collaboration of experts from many different fields, which allows them to come together and develop instruments to isolate and examine individual aerosols and explore single particle complexity in a way that has not been done before.

The center is also responsible for the development of a 30m wave flume, a chamber built to bring the ocean into the lab by using real seawater and simulating breaking waves to measure the aerosols and atmosphere created. Scientists from all over the world came to test ideas and use the equipment, take samples, and answer questions about photochemistry, atmospheric chemistry, and even marine biology.

Now, SOARS (Scripps Ocean Atmospheric Research Simulator) is the newest and largest piece of custom instrumentation that CAICE has seen. It is a warehouse-sized wave flume and wind tunnel created in collaboration with UCSD and Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

SOARS will be capable of simulating gale-force winds, polar and tropical oceans, induced phytoplankton and algal blooms, allowing for the chemical, physical, and biological study of the ocean and atmosphere.

The instruments that CAICE develops are driven by big questions. As Mickey Rogers puts it, “this is all working towards a better understanding of our planet, climate models, and how the climate is changing.”

Little does Bam the cat know, he is a namesake of some of the ingenuity and innovation within CAICE. A reminder of how CAICE has built the environment and equipment needed to understand the ocean/atmosphere in a way that the world hasn’t before.

And as Chris Jernigan puts it, “The ocean is a large part of the globe and is very important to get right. There are so many moving parts that there will always be new and interesting parts to investigate. The ocean and in particular the open ocean, far away from human influence, can act as a blank. This means a global background to understand what the climate was like before human influence. Having this background known well, we can then make more educated claims about the human driven changes to our climate. I joke that climate researchers are basically saving 7 billion lives a day. But truly, that’s pretty amazing”.