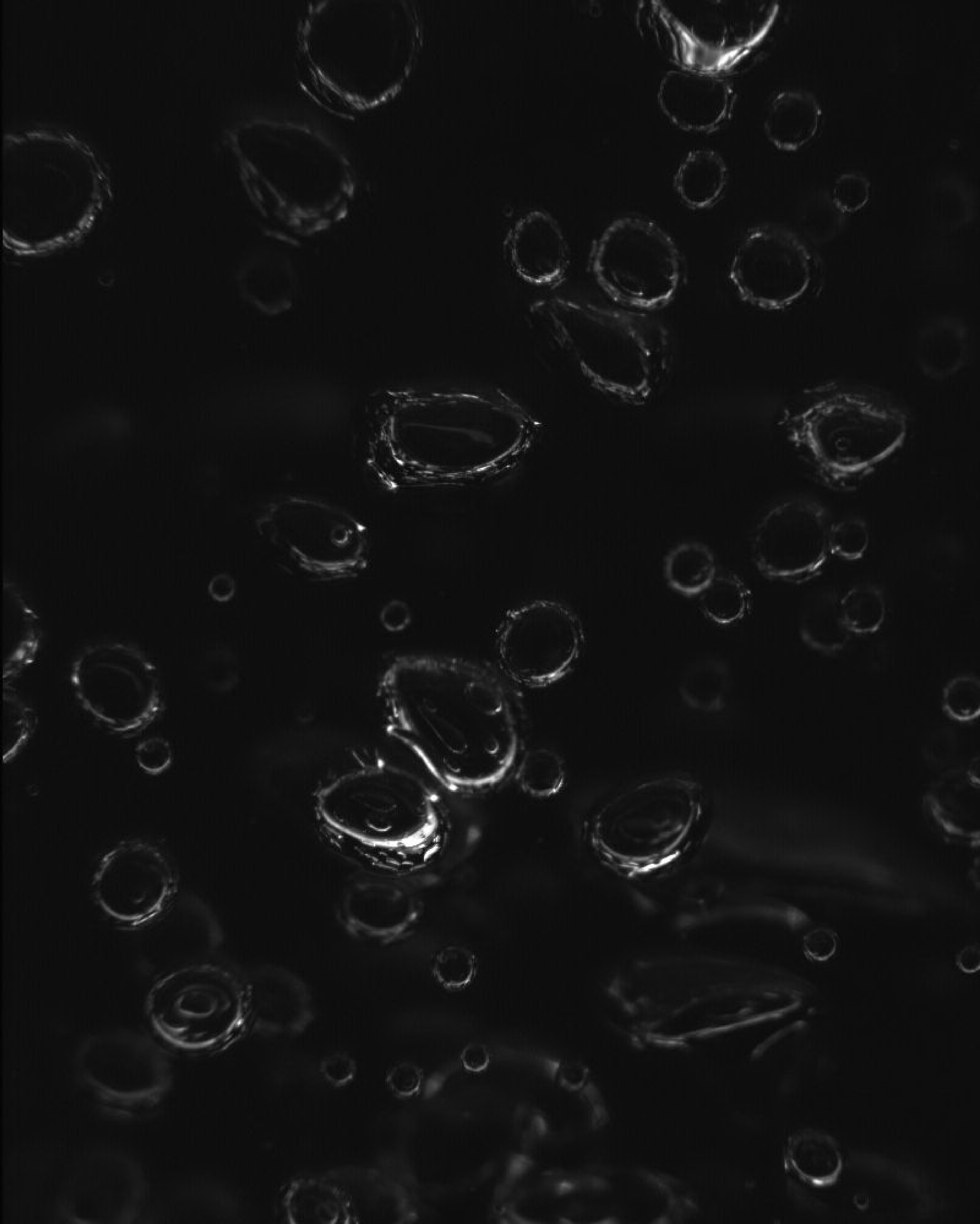

Ever enjoyed walking along the shoreline and listening to the roar of breaking surf? Underwater, the sound of breaking waves is the sound of air breaking into bubbles, each one of which rings with its own tone, large low and small high. Their chorus forms a hissing roar, and provides an audible clue to their number and size. This turns out to be important, because large bubbles in open ocean whitecaps are ephemeral and difficult to measure. We want to count all the bubbles in the sea, and we plan to do it by studying the noise they make. We have tried other methods. I have personally spent miserable hours on the deck of the Research Platform Flip during storms with my finger on a big red button, waiting to trigger an underwater camera just as a wave breaks overhead. That’s one of many good reasons to make breaking waves in a flume – we know when and where the waves are going to break.

So why the great interest in bubbles anyway? When the wind blows and waves break, they play an important role in exchange processes between the atmosphere and ocean. They enhance the transfer of gases across the air-sea interface, they change ocean color, they make underwater noise, they scavenge and transport organic surfactants and, when they rise to the surface, they create surfactant-enriched aerosols. The production of marine aerosols is, of course, the connection with CAICE. The Hydraulics Laboratory glass channel is the closest thing we have to an ocean in the laboratory. With the flume, we can create our own whitecaps and study the aerosols they produce. Then we can compare aerosols produced by breaking waves with other (more portable and convenient) production methods like frits and plunging water sheets.

And when we’re done with the flume? There will more laboratory work to do, but the great challenge will be to go back to sea, in ships and planes, to apply what we’ve learned in our laboratory ocean to the real thing.

Grant Deane, Research Oceanographer and Director of the Hydraulics Laboratory, SIO/UC San Diego